It’s been a while since I’ve written anything here but I’ve been pretty much on pause , thinking about objects in landscape, how we react and interact to them, how we hang and project memories and concepts onto them, how we enculture them. In my last post I introduced the idea of ‘gravity’ as a concept to explain how singular features in landscapes entrain our awareness in orbits of attention and interaction. Each individual’s orbit, following broadly the same law of cognitive gravity, will ultimately coincide with those of others, overprinting paths of attention and thus amplification of the significance of the feature. This in turn increases the singularity’s gravitational pull.

Last summer I talked obliquely about stones, both natural erratics and humanly placed megaliths, which both in the past, and through to the present, exercised a pull on individual awareness and collective culture. But the past month I’ve been thinking about hills.

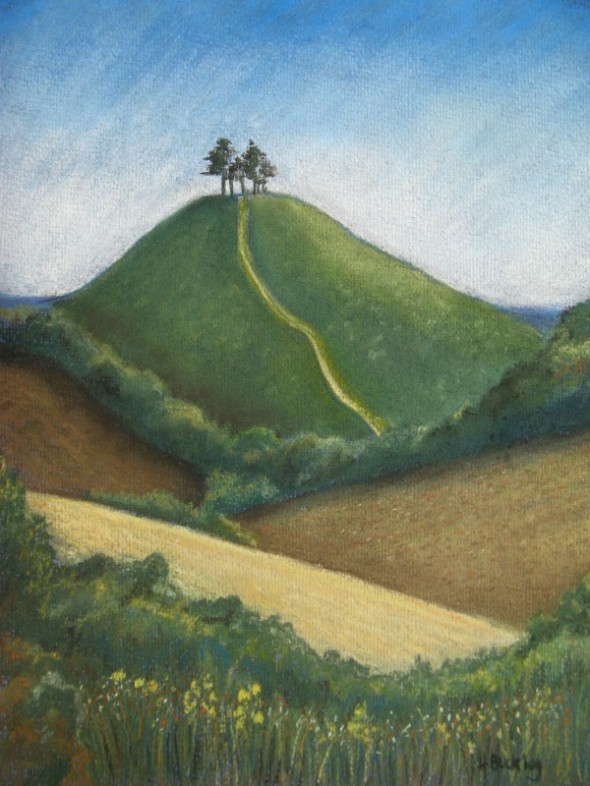

Not long ranges of rolling hills or dramatic escarpments, but isolated, distinctive hills.

Less imposing and dramatic than a single mountain peak, mesa or volcano, but contrasting with surrounding low relief landscapes and visible on the horizon at distances of 10 or 20 miles. The sort of thing quite rarely encountered in nature but which populate our imagination as type of archetype, such a child might draw if asked to crayon a ‘hill’ onto blank white paper. How do these topographic features play out in the dynamics of our evolutionary psychogeography? how can we start to define the gravitational relationship between human consciousness and these features?

On Good Friday we don’t have to think to far for a relevant example of a hill with enormous cultural gravity, albeit one we can’t actually demonstrate ever existed. From Early Medieval times, Good Friday was day the collective Christian imagination was firmly focused on the hill of Golgotha, the site of crucifixion. Now it doesn’t matter that Jerusalem’s 1st Century execution has never been formally identified by archaeology or that Golgotha more likely means “place of the skull” or “skull-cap shaped place” than “mount (or hill) of the skull” , or indeed that none of the four Gospels actually mentions the execution took place on a hill; the collective imagination has worked in such a way that the entire sequence of events leading to the crucifixion take place as a procession and orbit around a distinct topographical feature, an isolated hill surmounted by three wooden crosses. This ‘hill’ has been reproduced endlessly, as sacred imagery, 3D models and dioramas, even as actual small hills or calvaries created by the devout as a focus for their devotion. What interests me about this, is that literally forming the bedrock of a key moment in a 2000 year old religion with, currently, 2.2 billion adherents, is a topographic singularity which has developed an immense cultural gravity entirely divorced from any tangible physical reality. So with that in mind, I can’t help thinking how hills, knolls, and tumps potentially play a role in cultural landscapes in more routine ways.

Unlike mountains and dramatic isolated rocky outcrops (eg Uluru, Australia or Devils Tower, Wyoming) hills are relatively accessible, they invite approach, ascent and inhabitation. Unlike great eminences, hills are, from later prehistory, possible to engineer. Either by collective long term and (possibly) unconscious endeavour as in Tell mounds or in the creation of monumental ‘hills’ (barrows, larger mound such as Silbury and even pyramids) hills are possible to create. Hills are places which not only form landmarks on the horizon, but can be easily climbed and allow a view of wider horizons, they are scaled and can be contoured to integrate with the human realm, not the Olympian haunt of the Gods but a stage where, potentially, the human landscape and the otherworld overlap.

Before we journey into the mythic though, it’s worth considering, in evolutionary terms, what hills offered to mobile, hunter gatherer groups in our evolutionary past, from their earliest dispersal across the old world up the event of more settled ways of life.

In new, unknown, landscapes, tracking onto and heading directly for hills offered some distinct advantages. Faced with a horizon where to the north lies mountains, the east unbroken flatness and to the west a single hill, I can guess which direction offered the best survival choice. A hill suggests an isolated geological outcrop, whatever the sub-surface conditions of the plain, the hill will most likely be different. That means different rocks (maybe useful rocks), different soils (maybe nice free draining ones) different vegetation (maybe including good grazing for game) and the possibility of springs at the junction between the outcrop and surrounding geology. The hill also offers shelter and a view, after water and food, perhaps the two most important survival requirements in a new environment. These are facts of geographic reality, which exist independent of human thought and simply come about by the energetic dynamics of the hunter-gather way of life and the distribution of resources in landscapes. What we don’t know is when in our evolutionary journey a hill as a mental concept became sustained in human culture and when, as a result, a hill glimpsed on a distant horizon started to exert a gravitational pull on the group. Archaeologically we can think of ways to approach this but the important thing here is to realise the role this gravitational effect would have on human society and population success once it started to play a role. As a concept it breaks down the subject-object duality between the observer and the topographic feature and sets in train a dynamic that plays out between the two, has implications for how humans organise themselves in space, culturally embed knowledge in landscapes and successfully exploit environments.

From later prehistory onwards, hills (natural and man-made) have far less utility as niches for optimal use of landscapes, but are certainly not disregarded. They appear to be richly encultured as addresses for the unseen forces of the spirit world, the stages for heroic episodes in myth or even the direct creations of mythic beings. My local hills were all created when the Devis shovelled out spoil from the Devils Dyke, a deep natural valley, casting huge lumps of chalk here and there creating the distinctive downland summits. In the creation myths of Australia, hills are the chewed and spat out bones of miscreants gobbled up by the Rainbow Serpent. But one of my favourite examples is the Chocolate Hills of Bohol in the Philippines. Four creation myths exist for these wonderful, conical hills.

- Two giants fought for days hurling rocks at each other until they forgot their feud became friends.

2. A mighty giant called Arogo was heart broken after his true-love died and the hills are his tears.

3. After being poisoned by angry villagers, a giant buffalo who has been rampaging through farms, had an attack of diarrhoea. The hills are the dried remains of this monster’s faeces.

4. An overweight diet extracted all his stomach contents to win the hand of a beautiful woman.

The plurality of stories serves to illustrate that the mythic content encoded into these features is irrelevant. What is relevant is that humans seems to habitually do this. The bare hill at Uffington became the site of a dragon slaying, two hills in County Kerry became the Paps (breasts) of the Goddess Anu, the eminence at Dol, Brittany the site of the battle between St Michael and Satan, while Govarhan Hill was that raised by Krishna to protect the people from Indra. Pick a long inhabited landscape with a distinctive hill within it and there will be myth attached to it.

Hills, like the stones of my previous post, offer addresses for the embedding of cultural knowledge. We should be mindful of the role they may have played in past societies and of how we engage with and regard them today. In enjoying and conserving our own landscapes and helping others across the world to keep access to theirs, the deep and fundamental role they play as culturally pivotal, gravitational singularities needs to be considered too.